Here’s a weird one: Some notes on how to set up an environment and develop for DOS, today!

What is the platform?

All Intel CPUs starting with the 8086 support something called Real Mode. If you’ve dabbled with other retro computers and game consoles, Real Mode is the mode you’re looking for. This is in contrast to Protected Mode introduced on the 80286 and improved on the 80386 that provided a larger virtualized address space.

In Real Mode, the system has access to data across a 20-bit address space (even though the 8086 is a 16bit CPU). Effectively, the 20-bit address space offers 1 MB of addressable data (1,048,576 bytes, or 0xFFFFF). This 1 MB limit is sometimes known to as the A20 Line. Later x86 CPUs didn’t have this A20 limitation, but for compatibility, wrapping addresses at A20 could be enabled.

The notorious “640k should be enough” ‘ism of computers comes from the original design of the IBM PC. The IBM PC was designed around the limitations of the address space of the 8086 CPU. The addresses in the first 640 KiB (i.e. 0x00000 to 0x9FFFF) is allocade to RAM, and the rest is known as the UMA (upper memory area). On more advanced x86 processors, beyond the UMA is the HMA (high memory area, i.e. the first 64k above UMA) and the Extended Memory (up to 4 GB, completing the 32bit address space). Reference.

Within the UMA region, video memory tends to fall between 0xA0000 to 0xBFFFF (128 KiB), 0xC0000 to 0xDFFFF tends to be assigned to Device ROMs and RAMs (128 KiB), and 0xE0000 to 0xFFFFF is where the the System (BIOS) ROM tends to be (128 KiB). That said, even though these regions are 128 KiB, a 16bit pointer can only address 64 KiB at a time, making them more practical to use (hence why VGA mode was 320x200 and not 320x240 as the former is only 64,000 bytes (small enough to fit within 64 KiB)).

DOS Binaries (.com files)

This (Reference) finally explains the whole org 0x100 thing from way back. It turns out DOS (and CP/M) programs require that all programs start at the 256 byte boundary (meaning .com files can be a maximum of 256 bytes less than 65536 bytes in size). Other than that, .com files are raw and simple. Code and Data exist in the same blob.

The 256 byte region that prefixes the .com application is something called the PSP (Program Segment Prefix). One of the most notable features of the PSP is that this is how programs retrieved command-line arguments (up to 126 bytes worth), but there are some other features (including CP/M compatibility) baked in.

Intel Assembly vs AT&T Assembly

Depending on the compiler/assembler you choose to use, you may have to write your code in a different style. There are 2 styles of assembly code for the x86: Intel and AT&T.

Reference: https://www.ibm.com/developerworks/library/l-gas-nasm/index.html

AT&T Style

AT&T style is what GCC and a few obscure assemblers use (VASM). It’s notable for all registers requiring a % prefix, and all immediates (numbers) a $ prefix. It also uses c-style hex codes (i.e. 0xDEADBEEF).

The KEY difference here is that commands follow an OP SRC, DEST format.

# Text segment begins

.section .text

.globl _start

# Program entry point

_start:

# Put the code number for system call

movl $1, %eax

# Return value

movl $2, %ebx

# Call the OS

int $0x80

More info: https://github.com/yasm/yasm/wiki/GasSyntax

Intel Style

Intel style is the format used by the vast majority of assemblers. Unlike AT&T it requires no prefixes or suffixes, except when you want to use non-decimal encodings (i.e. hex, binary, etc). This is is where the infamous h suffix comes from.

The KEY difference here is that commands follow an OP DEST, SRC format.

; Text segment begins

section .text

global _start

; Program entry point

_start:

; Put the code number for system call

mov eax, 1

; Return value

mov ebx, 2

; Call the OS

int 80h

This is the style used by NASM, YASM, MASM, and most assemblers.

A86 Sytle

A86 is a variant of Intel style. It follows many of the same rules, except the numbers have some unusual encoding rules.

In A86, a number must always begin with a digit from 0 through 9, even if the base is hexadecimal. This is so that A86 can distinguish between a number and a symbol that happens to have digits in its name. If a hexadecimal number would begin with a letter, you precede the letter with a zero. For example, hex A0, which is the same as decimal 160, would be written 0A0.

Because it is necessary for you to append leading zeroes to many hex numbers, and because you never have to do so for decimal numbers, I decided to make hexadecimal the default base for numbers with leading zeroes. Decimal is still the default base for numbers beginning with 1 through 9.

Large numbers can be given as the operands to DD, DQ, or DT directives. For readability, you may freely intersperse underscore characters anywhere with your numbers.

The default base can be overridden, with a letter or letters at the end of the number: B or xB for binary, O or Q for octal, H for hexadecimal, and D or xD for decimal.

So unlike many other languages, a 0 prefix does not mean octal. Rather, it means hexidecimal, until told otherwise by a suffix.

; Text segment begins

section .text

global _start

; Program entry point

_start:

; Put the code number for system call

mov ax, 1

; Return value

mov bx, 2

; Call the OS

int 080H

A86 can be downloaded here: http://www.eji.com/a86/

NASM

NASM is the go-to standard for assemblers on x86 CPUs when Assembly is the go-to language (obviously GAS is the go-to choice if you use GCC, and LLVM if you use Clang). It’s so standard, it can be found in the regular Ubuntu repos.

sudo apt install nasm

For reference, there is a fork of NASM called YASM. The goal of YASM was to refactor and make a better NASM codebase, but both projects still gets regular updates, so it does not seem the projects haven’t ended eachother.

Side note: There is a suite of tools VASM that are primarily for 68000 family of chips (i.e. the Amiga and Atari ST), which includes a C compiler, but importantly the Assembler also supports 6502 and x86 among other things.

Recent GCC

Can be found here.

DOSBOX Usage

# Mount the specified folder as the C drive

mount c /home/mike/dos

# Unmount the drive

mount -u c

Alternatively, an application can be mounted and invoked automatically by passing it as an argument to DOSBOX.

dosbox myapp.com

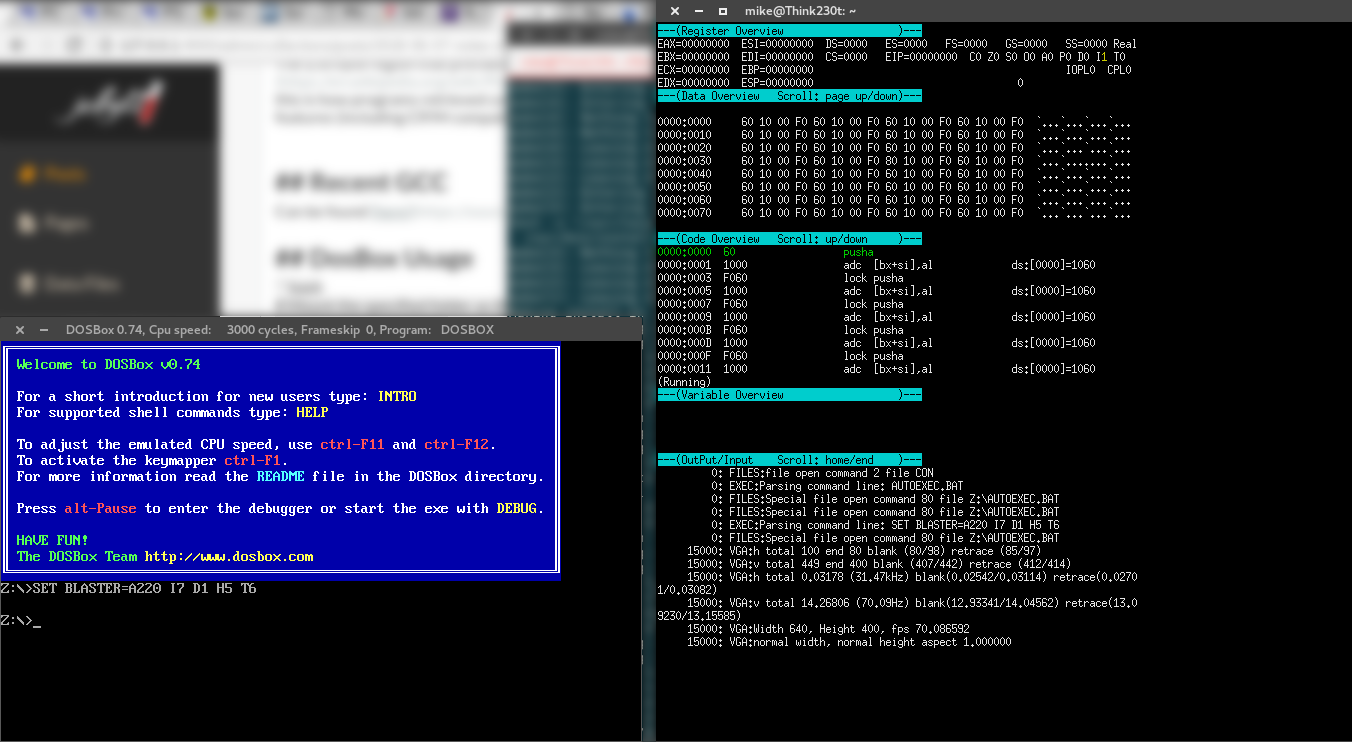

The DOSBOX Debugger

To get access to the advanced DOSBOX debugger, you unfortunately need to recompile DOSBOX.

Grab the latest source (It’s in an SVN repo, so just use the website):

https://www.dosbox.com/download.php?main=1

Then you have the choice to compile in regular and heavy debugger modes.

IMPORTANT: You will most likely want to uninstall the current version of dosbox you have installed, as you will be overwriting it.

# Uninstalling DOSBOX

sudo apt remove dosbox

# Regular Debug mode

./configure --enable-debug

make

sudo make install

# HEAVY Debug mode

./configure --enable-debug=heavy

make

sudo make install

You’re not done though. For whatever reason the standard shell that ships with Ubuntu is not entirely compatible with DOSBOX’s debug mode.

Instead, you must launch it from an xterm console.

Next, you’re going to want to stretch the console, make it much larger, as the debugger requires a lot of screen space. If you have a small-screen laptop like I do, this can fill the full left or right side of the screen.

Once sized, you can invoke DOSBOX as you would normally, and enjoy a large debug window alongside.

e